Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

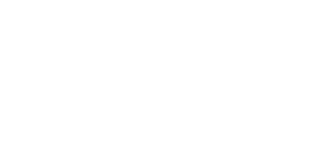

Importance of oral healthcare for hospitalised older adults

Oral healthcare of older patients is important in the hospital setting to reduce the risk of pain, malnutrition and pneumonia. This article looks at how oral health could be improved for older patients admitted to a geriatric ward.

Oral healthcare of older patients is important in the hospital setting to reduce the risk of pain, malnutrition and pneumonia.

Poor oral healthcare can greatly affect an older person’s quality of life due to pain, limited activities of daily living as well as social isolation.1,2 It is also associated with an increased risk of malnutrition,1,3,4 hospital-acquired pneumonia and aspiration pneumonia.3,5-8

Malnutrition is attributed mainly to decreased salivation, oral candidiasis and periodontal inflammation. Pneumonia is hypothesised to be caused by increased colonisation of bacteria in the oral cavity. There is also weak evidence for poor oral health contributing to stroke, dementia, cardiovascular diseases and mortality.9-11

Hospitalisation can impact on a patient’s oral health. One systematic review shows deterioration of oral health after hospitalisation in the form of increased severity of gingival inflammation and increase plaque accumulation.12 This is significant as chronic inflammatory processes are linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease.10 Moreover, plaque has been shown to harbour respiratory pathogens which can reach the lung through micro-aspiration and lead to lung infection.13

Many factors could contribute to the deterioration of oral health during hospitalisation, such as lack of knowledge of healthcare professionals about oral heath assessment, a proper management plan, shortage of staff, and concentration on the acute illness that brought the patient to the hospital in the first place.

According to the World Health Organization, oral health is the state of the mouth, teeth and orofacial structures that enables individuals to perform essential functions such as eating, breathing and speaking, and encompasses psychosocial dimensions such as self-confidence, well-being and the ability to socialise and work without pain, discomfort and embarrassment.

It also varies over the life course from early life to old age, is integral to general health and supports individuals in participating in society and achieving their potential.14

The World Dental Federation says oral care needs to be multifaceted so as to allow the patient the continued ability to speak, smile, smell, taste, touch, chew, swallow, and convey a range of emotions through facial expressions with confidence and without pain, discomfort, and disease of the craniofacial complex.”15

Therefore, there are different elements of oral health beyond treating dental carries or brushing teeth. It is also important to provide care and support, which in turn improves overall health and wellbeing. Understanding this concept will help to correct the idea of some edentulous seniors that once they loss all of their teeth, they are no longer concerned about oral health. Also, importantly, it will help to correct the understanding of healthcare professionals who think that oral care means tooth brushing only. It should also include care for the lips, tongue, palate, and cheeks and dentures care.2

Audit on oral healthcare of older patients

The aim of the audit was to improve oral health of older patients admitted to a geriatric ward.

Objectives

- To assess nurses’ attitudes towards oral health

- To determine patient preference of frequency of oral care to be done by healthcare professionals.

Methodology

This was a one-day project. All older patients admitted to the geriatric ward who were conscious and oriented were interviewed after giving verbal consent. Date of birth was taken from the medical record system in addition to the presence of dementia and confusion. The patient was asked if they had their mouth care on that day. They were also asked whether they did their mouth care themselves, or if it was done by a nurse or allied health professional. Then they were asked how frequently they wished for dental brushing to be done in a 24-hour period.

The assigned staff nurse of the patient was also asked to document if they had carried out mouth care for the patient.

Result

The total number of patients included in this audit was 21 patients. This included 11 males and 10 females (Figure 1). The age group of the cohort was as following : 62% aged >80 years, 33% aged 70-80 years old and 5% aged 60-70 years old (Figure 2).

Approximately 29% of the study population had dentures (Figure 3). Confusion was diagnosed in six patients ( 29%), and four of them had a diagnosis of dementia (Figure 4).

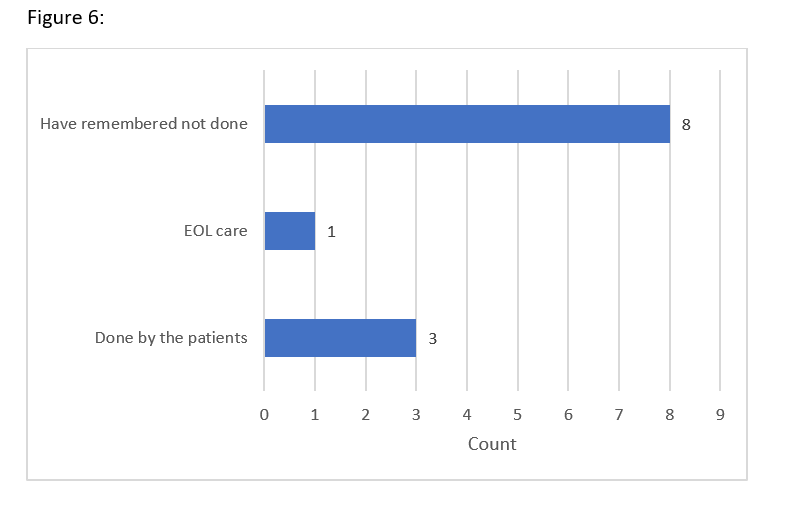

Approximately 52% of the study cohort could remember whether dental cleaning had been done or not and 14% said they could not remember (Figure 5). Among those who did remember about dental cleaning, three of them did it by themselves and eight of them said they didn’t have dental cleaning (by themselves, nurses or allied health care). One of them said he was waiting for his daughter to bring in his toothpaste and brush so could start brushing his own teeth.

Among those who didn’t remember, two of them did not receive mouth care and one patient did but it was not documented on the patient chart. One patient was in end of life (EOL) care and had mouth care every two hours (Figure 7). This was documented in the fluid chart with no specific chart for dental care.

When assessing patient preference to have oral hygiene, seven patients preferred three times a day, three preferred twice a day, two preferred once a day and two preferred not to have dental cleaning at all (Figure 8).

Discussion

This audit suggests that a number of healthcare professionals would view oral healthcare as dental cleaning only. Not many will use a specific chart for documentation of mouth care and there is a lack of guidance and training on how to manage oral care for patients who are confused or are at high risk for complications. For our audit, most dental cleaning was conducted by allied healthcare professionals so this is where more training should be made available.

Recommendations

- More training is needed about inpatient mouth care for nurses, physicians and allied health professionals

- There should be a poster in the ward demonstrating the different components of mouth care.*

- There should be an education leaflet and poster about how to identify and manage problems in the mouth.*

- Re-auditing will be done after one year.

* This could be arranged with the Mouth Care Matters team who already provide training for 80 trusts in England and they have posters and education material which can be used to improve the service.

Dr Majdah Al Rushaidi, Trust doctor, Elderly Care Department at James Cook University Hospital (JCUH), Middlesborough

References

- RCS 2017. Improving older people’s oral health. ENGLAND

- Masood M, Newton T, Barki NN, et al. The relationship between oral health and oral health related quality of life among elderly people in United Kingdom. Journal of dentistry 2017; 56, 78-83

- Poisson P, Laffond T, Campos S, et al. Relationships between oral health, dysphagia and undernutrition in hospitalised elderly patients. Gerodontology 2016; 33, 161-168

- MCM. 2016. Mouth Care Matters A gauide for hospital health care profesionals [Online]. Available: https://mouthcarematters.hee.nhs.uk/2020/01/06/mouth-care-matters-guides-launched/ [Accessed 25/03 2022].

- Liu,C, Cao Y, Lin J, et al. Oral care measures for preventing nursing home‐acquired pneumonia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018

- SJjogren P, Nilsson E, Forsell M, et al. A systematic review of the preventive effect of oral hygiene on pneumonia and respiratory tract infection in elderly people in hospitals and nursing homes: effect estimates and methodological quality of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2008; 56, 2124-2130

- Terpenning M. Geriatric Oral Health and Pneumonia Risk. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2005; 40, 1807-1810

- Kanzigg LA, Hunt L. Oral health and hospital-acquired pneumonia in elderly patients: a review of the literature. American Dental Hygienists’ Association 2016; 90, 15-21

- Daly B, Thompsell A, Sharpling J. Evidence summary: the relationship between oral health and dementia. British Dental Journal 2017; 223, 846-853

- El Kholy K, Genco RJ, Vab Dyke TE. Oral infections and cardiovascular disease. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2015; 26, 315-321

- Maeda K, Mori N. Poor oral health and mortality in geriatric patients admitted to an acute hospital: an observational study. BMC Geriatrics 2020; 20, 26

- Terezakis E, Needleman I, Kumar N. The impact of hospitalization on oral health: a systematic review. Journal of clinical periodontology 2011; 38, 628-636

- Steel BJ. Oral hygiene and mouth care for older people in acute hospitals: Part 1. Nursing Older People 2017; 29

- World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/oral-health#tab=tab_1

- Glick M. Williams DM, Kleinman DV. A new definition for oral health developed by the FDI World Dental Federation opens the door to a universal definition of oral health. British Dental Journal 2016; 221, 792-793.