Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia1 and is a major cause of stroke. One in every five strokes in the UK is due to known AF.2 Compared with non-AF strokes, AF-related strokes are associated with higher mortality rates3, greater disability, longer hospital stays4 and a lower rate of discharge back home.

Progression of atrial fibrillation is thought to be driven by structural changes in the atria, including electrical, contractile changes, known as atrial remodelling.5 AF tends to progress from paroxysmal (self-terminating, usually within 48 hours) to persistent (non-self-terminating or requiring cardioversion), long-standing persistent (lasting longer than one year) and eventually to permanent (accepted) AF.

In 2019, a new coalition called the National CVD Prevention System Leadership Forum (CVDSLF), led by Public Health England and NHS England, announced the first ever national ambitions to improve the detection and treatment of atrial fibrillation, high blood pressure and high cholesterol (A-B-C) – the major causes of cardiovascular disease (CVD).6

Made up of 40 organisations, the agreed ambitions for atrial fibrillation were:

- 85% of the expected number of people with AF are detected by 2029

- 90% of people with AF who are known to be at high risk of a stroke to be adequately anticoagulated by 2029.

Recorded AF prevalence in 2017 to 2018 was 1,113,553, which is just 79% of the expected number of people estimated to have AF.

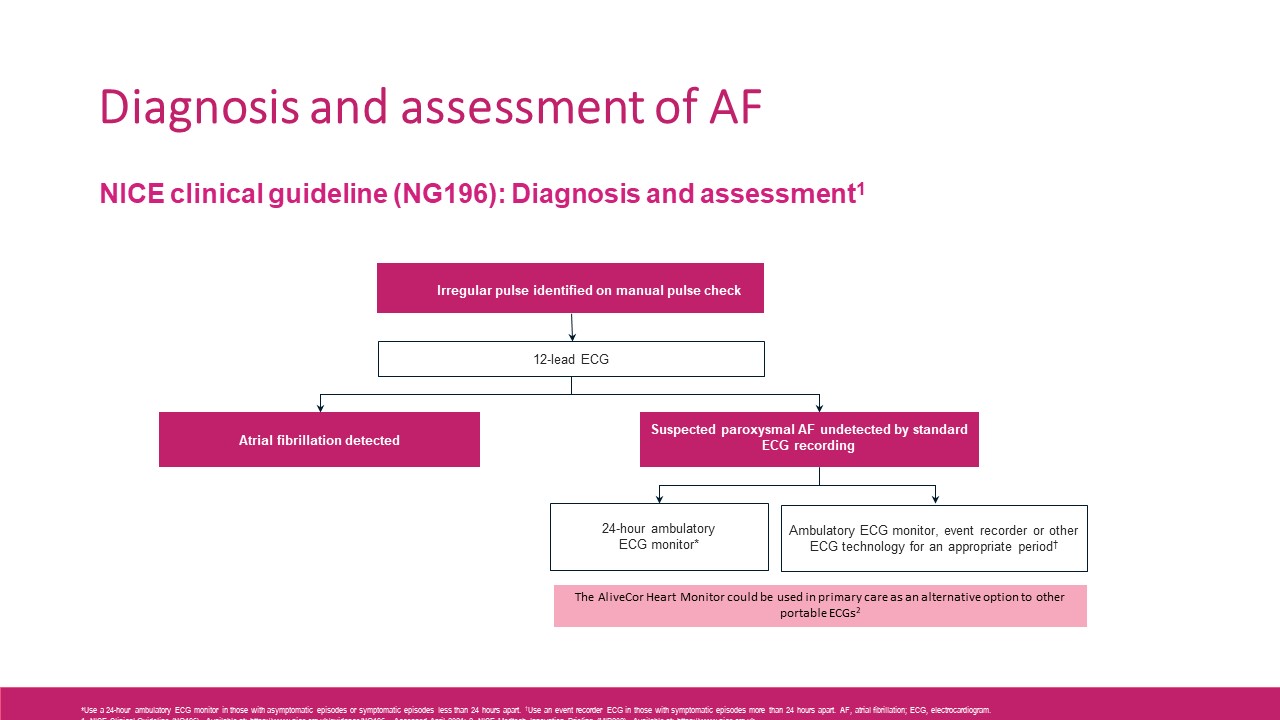

Diagnosis and assessment of AF

NICE guidance recommends performing manual pulse palpation to assess for the presence of an irregular pulse if there is a suspicion of atrial fibrillation.7 This includes people presenting with any of the following:

- breathlessness

- palpitations

- syncope or dizziness

- chest discomfort

- stroke or transient ischaemic attack.

It also recommends performing a 12‑lead electrocardiogram (ECG) to make a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation if an irregular pulse is detected in people with suspected atrial fibrillation with or without symptoms.

In people with suspected paroxysmal atrial fibrillation undetected by 12‑lead ECG recording:

- use a 24‑hour ambulatory ECG monitor if asymptomatic episodes are suspected or symptomatic episodes are less than 24 hours apart

- use an ambulatory ECG monitor, event recorder or other ECG technology for a period appropriate to detect atrial fibrillation if symptomatic episodes are more than 24 hours apart.

The number of patients diagnosed with AF each year is increasing.8 Preventing AF-related strokes is also a recognised priority across NHS England and there is a national programme across England to tackle this issue.

Up to £40 million investment has been made into ‘Detect, Protect and Perfect’ pathway initiatives which will help identify people with AF and move them onto effective and appropriate treatment.9

- Detect – Raising public awareness of AF and the importance of pulse rhythm testing to identify those with undiagnosed AF

- Protect – Supporting healthcare professionals to offer optimal anticoagulation medication to all those who would benefit

- Perfect – Supporting patients with their anticoagulation medication and supporting clinicians to review patients with AF.10,11

Use of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation

A Lancet meta-analysis showed oral anticoagulants had a favourable benefit-risk profile versus warfarin in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. The relative efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants was consistent across a wide range of patients.12

Both safety and efficacy are important in the management of AF but the primary goal of oral anticoagulation in patients with AF is stroke prevention.

Right now bleeding is the dominating topic, but is this appropriate? Bleeding can usually be managed, whereas even if stroke is not fatal it can be severely disabling. We need to re-emphasise that stroke prevention should be the focus of anticoagulation use in patients with AF.

In addition, not all clots are the same. Thrombi in patients with AF are predominately fibrin-rich whereas thrombi in coronary artery disease (CAD) tend to be platelet-rich. Anticoagulants reduce the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Aspirin and other antiplatelets, inhibit aggregation of thrombi caused by CAD, but do not impact upon fibrin production.

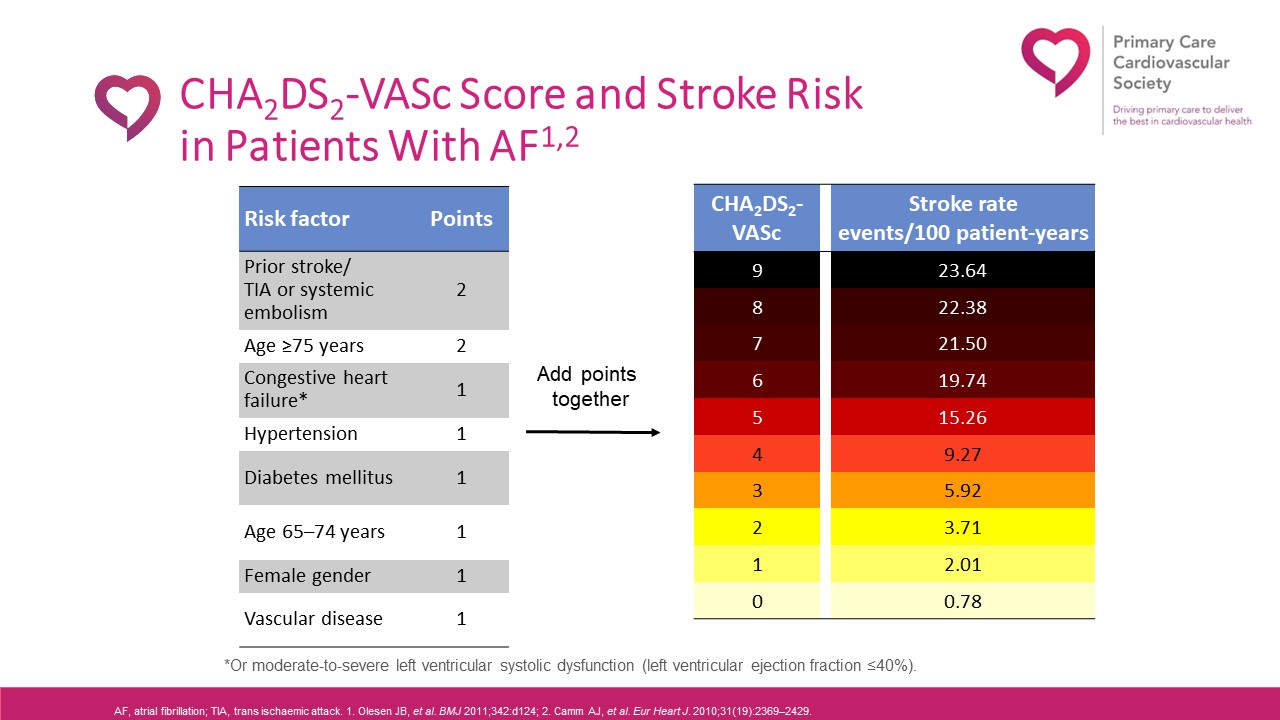

NICE guidance states that the CHA2DS2VASc score, which calculates stroke risk for patients with atrial fibrillation, should be used to assess stroke risk in people with:

- symptomatic or asymptomatic paroxysmal, persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation

- atrial flutter

- a continuing risk of arrhythmia recurrence after cardioversion back to sinus rhythm.

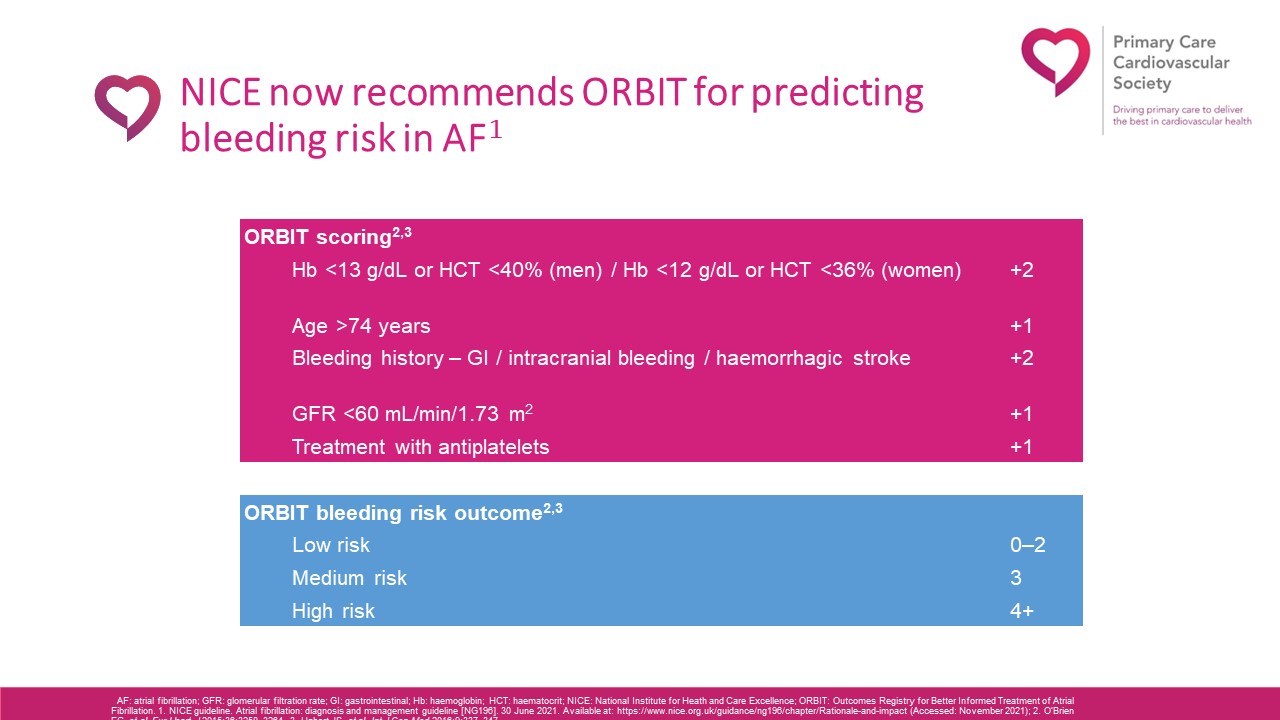

NICE says to assess the risk of bleeding when considering starting anticoagulation in people with atrial fibrillation and reviewing people already taking anticoagulation.7

It says to use the ORBIT bleeding risk score because evidence shows that it has a higher accuracy in predicting absolute bleeding risk than other bleeding risk tools. Accurate knowledge of bleeding risk supports shared decision making and has practical benefits, for example, increasing patient confidence and willingness to accept treatment when risk is low and prompting discussion of risk reduction when risk is high. Although ORBIT is the best tool for this purpose, other bleeding risk tools may need to be used until it is embedded in clinical pathways and electronic systems.

Overall, the risk of stroke without oral anticoagulation exceeds the bleeding risk with treatment. Bleeding risk should not be used to exclude patients from OAC therapy, but exercise caution and review regularly if bleeding risk is high.7,12-14

If a decision is made not to anticoagulate, then that patient will be at greater risk of stroke with potentially greater healthcare resource needs and costs to the wider health system.12-14

Often the considerable risk of stroke without oral anticoagulant therapy exceeds the bleeding risk of treatment, even in the elderly, patients with cognitive dysfunction, and patients with frequent falls or frailty.

NICE recommends to discuss with these patients that for most people the benefit of anticoagulation outweighs the bleeding risk and that careful monitoring of bleeding is important.7

Ongoing monitoring should include at least annual review of renal profile, full blood count and liver function tests. Exceptions include six-monthly review if creatinine clearance 30–60 mL/min and/or aged >75 years and/or frail and a three monthly review of renal profile if creatinine clearance 15–30 mL/min. Check for side effects/bleeding issues and patient adherence to therapy at each routine appointment.

To conclude, direct oral anticoagulants are the preferred choice for the vast majority of patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. NICE states that when initiating a DOAC consider potential renal impairment, difficulties in swallowing and adherence and dosing frequency.

This article is based on a presentation given at the GM Conference: Health and Ageing in a post-Covid NHS

Professor Ahmet Fuat is a GP , GP Appraiser and GPSI Cardiology, Darlington, Co. Durham and Honorary Professor of Primary Care Cardiology, Durham University

References

- Hindricks G, et al. Eur Heart J 2020; 42: 373–498

- ABPI Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Initiative. NOACs: innovation in anticoagulation – optimising the prevention of AF-related stroke. ABPI SAFI, 2014. Available at: https://www.heartrhythmalliance.org/files/files/aa/for-clinicians/140401-ar-1-NOACs%20Innovation%20in%20anticoagulation%20report.pdf/ (Accessed: November 2021)

- Lamassa M, et al. Stroke 2001; 32: 392–398

- Jørgensen HS, et al. Stroke 1996; 27: 1765–1769

- Camm AJ et al. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 2369–2429

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-preventing-cardiovascular-disease/health-matters-preventing-cardiovascular-disease#atrial-fibrillation (accessed 15/03/23)

- NICE Clinical Guideline (NG196). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG196. Accessed September 2022

- NHS Digital: Quality and Outcomes Framework, 2015–20. Available at; https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/quality-and-outcomes-framework-achievement-prevalence-and-exceptions-data (Accessed: November 2021).

- NHS England – News. Thousands spared strokes thanks to new NHS drug agreements. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2021/11/thousands-spared-strokes-thanks-to-new-nhs-drug-agreements/ (Accessed: November 2021).

- The AHSN Network. Available at: https://www.ahsnnetwork.com/about-academic-health-science-networks/national-programmes-priorities/atrial-fibrillation/, accessed December 2018;

- The AF Toolkit. Available at http://www.londonscn.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/detect-protect-perfect-london-af-toolkit-062017.pdf, accessed November 2018c

- Ruff C, et al. Lancet 2014; Volume 383, Issur 9921: 955-962, 2014

- Hindricks G et al. Eur Heart J. 2020;43:373–498. 2. NICE. Atrial fibrillation: diagnosis and management. NG196. 2021. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng196 (Accessed: November 2021)

- Steffel J, et al. Europace 2021;00:1–65; 4. Stroke Association. Current, future and avoidable costs of stroke in the UK. January 2018. Available at: https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/costs_of_stroke_in_the_uk_economic_case_interventions_that_work.pdf (Accessed: November 2021)